|

Increasing salinization is the reality for coastal landscapes worldwide. Saltwater travels over the land, under the ground, and through surface water channels. However, hydrologists have studied the pathways of over, under, and through separately, limiting the full understanding and prediction of where salt is delivered in coastal landscapes. Human modifications additionally alter these pathways and in turn, alter the delivery of salt into freshwater landscapes. Holistically studying the hydrology of SWISLR is needed where the pathways over land flow, underground, and through surface water channels are studied together with the alteration of human modifications included.

This group is writing a perspectives piece to present a conceptual framework that calls for this integrated study of water flow and human modifications. Multiple case studies will be highlighted in the paper as reasons to study SWISLR holistically and as potential ways to use the conceptual framework. The paper will wrap up by discussing the future of our coast and recommendations for studying SWISLR hydrology. In today’s webinar, a few potential case studies were presented. Greg Noe talked about the “Through” and the heavily modified Savannah River. Justine Neville presented a case study of saltwater intrusion into small man-made channels in southeast North Carolina due to flow control structures. Alex Manda showed us projects measuring the salinity of agriculture fields in Coastal North Carolina due to the connectivity of agriculture drainage canals. Lastly, Marcelo Ardón shared his experience with saltwater intrusion in the Albermarle-Pamlico Peninsula in coastal North Carolina in a restored forested wetland. Additional proposed case studies are Southern New England, the Eastern shore of Virginia, and the Gulf Coast.

0 Comments

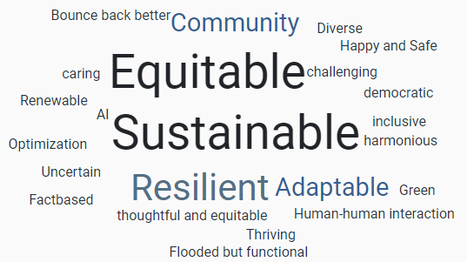

Torry Bend and Kiera O’Donnell talk through the Stories of Change project, from where it started to how it has evolved to be larger than the original pitch. The original pitch had an underlying goal of engaging with coastal stakeholders in a meaningful way. The team wanted to create a space where people could be open and honest about climate change while still being informed about potential risks and solutions of SWISLR. They found that stories were a potential way forward with this project. Stories can be a place to hold grief, they can be a safe way to share information, and they can be used to create idealized futures and situations. To start the webinar, everyone was asked “If you were to present the version of the future in the most idealistic terms, what does that look like?” Kiera and her team of Duke students have worked through SWISLR-related papers that were associated with a social science discipline. They are working to uncover who is studying SWISLR within the social science sphere, where are SWISLR interviews and surveys taking place, how is SWISLR impacting coastal communities, and what are the means of response to SWISLR impacts. The past semester was all about extracting information from SWISLR social science research, and now the team at Duke is working on analyzing the data and synthesizing the information they worked to pull out of the literature. They specifically will be looking at what questions are being asked in these papers and surveying the surveyors to ask them what questions should be asked. To find out more about this project you can see their first semester findings described in this blog post: https://apnep.nc.gov/blog/2024/01/22/saltwater-intrusion-sea-level-rise.

Through engaging with community members, Torry has been able to create and collaborate on 4 different projects and has taken the original goal of co-creating stories of change to the next level. Torry found the original questions and goals laid out during the all-hands meeting were becoming stretched and changed based on who she was talking to and the timing of when people were able to talk. The first project is working with K-12 students to write and create resiliency fables to give the students power in their future and an outlet for their grief and worry surrounding climate change. The second project is creating a collective of people working in puppetry and climate change so as opportunities come up there is a network of people working in this sphere that can be connected to the project in question. The third project is making a documentary on farming in Princeville, a coastal North Carolina town. The farmer Torry is working with talked about their connection to the land, the changes they have made throughout their life, and the changes they will have to make in future SWISLR-induced farm fields. The last project is a short live puppet show on moving away from the coast with the intent to connect an art form to information. Although migration is a tough topic to talk about, the connection to art and puppetry is a creative way of softening some of the anxiety surrounding it. All these projects came out of the idea that stories can be a powerful tool to talk about anxieties surrounding climate change. We finished the webinar with a discussion on public spaces and factors that have facilitated safe spaces to share ideas and thoughts about climate change. You can watch the presentations and the discussion here. https://youtu.be/E924S_bvdBA For the December webinar we were joined by Henry Yeung and Dr. Justin Wright to talk about the many aspects of ghost forests. Henry Yeung is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Virginia, studying plants and climate change using remote sensing. Dr. Justin Wright is a plat ecologist interested in uncovering the causes of ecosystem patterns. Both are interested in ghost forests.

Henry has been able to create a fairly accurate model to predict where dead trees are located based on spectral imagery from the sky. He has also been able to identify the areas that are more difficult for the model to identify. With this accuracy, he has been able to apply the model across the entire eastern coast (Virginia to New Hampshire). Using the large area of tree mortality, Henry could start identifying trends in the data. Henry has been able to identify that mortality varies strongly with elevation but differs across regions. Most mortality happens below 10 meters of sea level and the Mid-Atlantic wetlands are experiencing substantial forest mortality. Specifically, the states of Maryland, New Jersey, and Virginia are experiencing the most freshwater forest mortality. Using this model we have increased our understanding of U.S. east coast ghost forests, providing a method for other areas to do the same. Looking at ghost forests at these large scales provides us with generalizable information, however, it is potentially missing the landscape-specific changes that can cause increased or decreased forest mortality. Dr. Justin Wright has decided to create a team focused on understanding the history of places where we see these large swaths of ghost forests. In general, he has found that when researchers are trying to understand why land has been heavily impacted, our immediate thought is to the present - what are the species located there, what is the hydrology of the area, etc. But what we are seeing is the history of the landscape that is influencing trends present to this day. Therefore, a newly funded project to work with the Forest History Society will be compiling the history of coastal North Carolina which will highlight the history of the ghost forests that Henry is seeing from remote sensing. The big question now, is how do we scale up the history of landscapes impacted by SWISLR? Both projects are focused on ghost forests, and although they cover very different aspects of tree mortality, they are both focused on understanding the patterns of mortality and how we can potentially protect, or at least predict, the loss of our forested wetlands. Spencer Rhea and Alex Smith joined us to share updates on their SWISLR projects created at the All-Hands meeting this past May. Spencer started by sharing his project “S.T.E.W.P. - Salting the Earth with Purpose” (name yet to be finalized) focused on understanding how SWISLR affects carbon emissions in coastal wetlands, with a focus on how soil properties can mediate the response. Alex Smith followed up with the “G.Y.S.T.” project focused on how we can adapt ecosystem models to SWISLR field work going on and how field work can potentially be adapted to inform models. You can watch this recording posted in the SWISLR Seminars page.

As Spencer introduces his project, he shared with us that wetlands store a lot of carbon due in part to the soils that allow wetlands to hold onto the carbon for a long time. With global climate change these carbon stocks are under threat and many of our wetlands are disappearing under sea level rise. The effects of saltwater intrusion into wetlands and soils is variable and there are many different effects that can compound on each other. To gain a better understanding of SWISLR effects on soils he collected soil samples from other SWISLR RCN member’s research sites and compared the soil and chemical properties between salt exposed sites and protected sites. This project is still in the beginning stage and Spencer will investigate wetlands soils further through a “Common garden experiment” and a “Common substrate experiment”. Through this work Spencer wants to identify what soils are most resistant to SWISLR and welcomes other soil researchers to get involved in this soil examination! Alex further discusses the complexity of SWISLR impacts to ecosystems and explains how these complex interactions compounding on each other require complex and innovative models. To arrive at these innovative models we first need to understand the popular adaptable models available. Through a synthesis of adaptable terrestrial models Alex arrived at ELMs, specifically the Energy Exascale Earth System Model (E3SM), a model that simulates coupled processes and interactions among water, energy, carbon, and nutrient cycles. However, the ELM does not include detailed hydrology, ecology, or biogeochemistry - all traits that we would need for modeling SWISLR. But, this model is adaptable and modules can be added to refine the model for SWISLR. Alex talks through the modules of FATES and PFLOTRAN and their pros and cons with modeling SWISLR. The current inclusion of coastal habitats in ELM, the adaptability of ELM through modules, and the simplicity in the structure of the model make a great case for why we should use ELM to model SWISLR. In addition, field studies could better inform these models. Therefore, Alex is completing a literature review of SWISLR field studies to identify what researchers are collecting and the traits that would be important to include in a model. Studies like G.Y.S.T. and S.T.E.W.P. are helping to inform our SWISLR RCN on how we are and how we should be collecting ecosystem disturbances due to SWISLR. As we, as researchers, continue to complete experiments and collect data, there should be a concerted effort to identify and abide by a standard set of methods. Friday SWISLR webinars are happening again this school year! SWISLR Seminars will be once a month, each one focused on a project that came out of the SWISLR All-Hands meeting. Many people during the All-Hands meeting said that the SWISLR RCN can help their projects by providing connections to people or to data outside of their social network. Therefore, each project will have a chance throughout the school year to host a SWISLR Webinar and a discussion that will help further their project.

The Projects and their project leads:

For this first webinar each project got a chance to highlight what they proposed at the All-hands meeting and what has been accomplished since then. You can check out these pitches by watching the recording of this webinar on youtube. After each project lead, or project representative, introduced their project, we had breakout groups to further discuss what has been going on within the working groups. In these breakout groups people shared ideas and data sources. The S.T.E.W.P. project now has an additional soil sampling site, Stories of Change has some more people to talk to about the changes they are observing, and the SWISLR RCN has some new members joining the list serv! I am looking forward to hearing more about these projects in the coming months, and can’t wait to see what connections grow from them. A commonality that we all share is data – if you don’t collect your own data you often use publicly available data to find information through national or regional datasets. Working with big publicly available data has introduced the need for some guiding principles in order to protect sensitive data and allow access to everyone equitably. One such set of principles are the FAIR data principles. This acronym stands for findable, accessible, interoperable, and reusable and these guidelines put emphasis on enhancing the ability of machines to automatically find and use the data, in addition to supporting its reuse by individuals. Without these pieces it is hard for data reuse to happen. Reuse is important in research because many people rely on syntheses, regional generalization, and comparing methods or results. Reuse and access is also important to community members and practitioners so they can make decisions using the best data possible. Specifically with SWISLR, FAIR data practices (https://www.go-fair.org/fair-principles/) are necessary if we want to make general statements of the issues SWISLR causes. There are really hard to solve problems happening right now, and in order to come up with resilient solutions, it is more beneficial if we can use data across regions and disciplines.

Organizations such as NSF, NASA, and journals (e.g. AGU) are creating policies where researchers are required to share their data and make the data publicly available in data repositories. There is a large landscape of data repositories available on the web that can make it harder to find the source of data you are looking for. Although they are helpful for housing data and making them publicly available, the number of repositories available can make it harder to know where to look for the data you are trying to find. There are efforts to combine these repositories as data atlases that constrain the geography or google data that houses the links to these data sources. However, they do not cover the full depth of data available on the web. Given this, Dr. Anna Braswell has asked – “How can we make data more discoverable?” One way is that we can create a centralized data repository for all data like NOAA’s National centers for environmental information (https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/) or the European Marine Observation and Data Network (https://emodnet.ec.europa.eu/en). However, this requires a lot of time, space, and money that is not readily available. Another option is to require improvements to the information included with the open data so it can be more findable for systems like google data that scrape the web for you when you search. But this takes a lot of buy in from all the repositories housing data and researchers who publish their data. Although this is doable, it will take time. Finally, one option forward is to create a community around data. To achieve this, Dr. Braswell is creating a site where people can create posts about data they use and post questions they have about data availability and useability: https://copecomet.github.io/Coastal-Data/. The goal of this data curation service is to create a community around data and help improve the ways in which we use and find data. The most recent SWISLR webinar discussed ecological system shifts throughout the NACP. Justin Wright and Aeran Coughlin introduced us to their work on plant and microbial community change in the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. The RCN hopes to synthesize the ecological impact of SWISLR. Existing studies are typically site-specific and species-based, limiting the possibilities for generalizations. However, a syntheses of existing studies will help determine what to expect and help develop best-practices for future coordinated research. Therefore the second half of the webinar was a discussion about what people are studying and how traits are being linked to SWISLR induced changes.

Justin Wright starts off by talking through how SWISLR is inducing changes not only along the coast but affects inland plant communities due to human alterations. Specifically in the Albemarle-Pamlico peninsula, the drainage networks allow for salt to move inland. The wright lab has looked at how plant communities have changed because of this salt incursion into the peninsula. They found that species composition has shifted to varying degrees, but were not quite sure what the causes of these changes were. There was some hint that salt and elevation was correlated to the composition shifts, however the relationships were stronger for plant-traits such as basal area (Anderson et al. 2022). These findings indicate that SWISLR is responsible for the drastic ecosystem shifts into the transient state of ghost forests that are seen throughout the NACP. However, the mechanisms of these changes is not entirely known since correlations do not prove that salt is responsible for composition changes. So, Aeran is diving deeper into these interactions to identify why plants are reacting to salt coming into the soil in the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge. They are focusing on plant-soil interactions and have already found that the microbial soils are important for tree and shrub growth, with forest soils in the Alligator River being primed for shrub growth. Being at the start of their dissertation, Aeran has many more questions to answer and has primmed the RCN to think about how to study plant interactions moving forward. The RCN contains more than just plant ecologists, and people are thinking about many aspects of SWISLR from human land use to coastal hydrology. Most plant ecologists who were in the room said they mostly study community composition and measurements of function aren’t as prevalent. Many use indicator species (like Justin and Aeran) to identify ecosystem changes due to SWISLR but it is hard to connect species to salinity specific stress since a lot of plant trait changes are the same regardless of whether a tree is stressed by inundation or salinization. A paper by Keryn Gedan and Eduardo Fernandez-Pascual was highlighted as an example of linking plant traits to salinization. Another example of linking plant traits to salinization is Serina Wittyngham’s work at VIMS. They are curious about what constrains the lower limit of Phragmites in the salt marsh since the upper limit is better understood. They are measuring plant traits and rhizome starch content of Phragmites to see how treatments such as salt and herbicide influence the energy stores and ability for spread. You can watch the Wright lab talk and the summary of the discussion rooms on youtube. The discussions so far have been 15-30 minutes long, often cutting some connections and thoughts short. We hope you all will continue these discussion at the upcoming all-hands meeting! We took a break from the regular format of our webinars to host a Show-and-Tell! This format was to help us start talking about the 3rd theme: How are water management and climate change interacting to determine the magnitude, extent, and duration of saltwater intrusion within and across the NACP? Although we know that humans have altered the hydrology across the coastal plain, the extent to which human activities lead to variation in SWISLR impacts is not well known. Regional differences in water management practices create areas of “weird” water movement since human infrastructure can potentially constrain the natural hydrological processes through flow control technologies. Variabilities within the water infrastructure makes the interactions between water management and water harder to understand regionally. When predicting the timing, magnitude and duration of saltwater intrusion and sea level rise “bathtub” models are typically used that assume topography as the dominant driver of vulnerability. However, the coastal plain ecosystem is dependent on human decisions of water management and infrastructure. Therefore, to better understand the full impact of SWISLR we require models that integrate sea level rise, rainfall-runoff relationships, evapotranspiration, natural geomorphology, water infrastructure (canals systems, dikes, levees) and water management (pumps, check dams, irrigation, groundwater extraction). In the SWISLR Show-and-Tell we invited RCN members to tell us about the weird water where they work and live: Some alternatives to photos were Ashley Helton's coastal viewer, Xi Yang's drone video, and Jean-Christophe Domec's site info. You can watch everyone's description of their photos here.

The SWISLR RCN has now hosted three webinars covering different themes of research related to saltwater intrusion and/or sea level rise. This webinar covered the question of: Where are ecosystems vulnerable to SWISLR induced transitions along the NACP and how can we predict vulnerability? You can find a recording of this seminar here.

Dr. Elliott White starts us off by talking about what we can do, and what we can’t do with remote sensing. Modeling has shown us that we are losing coastal wetlands overall (Osland et al. 2022). There are multiple threats to coastal wetlands that lead to increasing salinization of surface groundwater which in turn yields declines in coastal wetlands. There is also spatiotemporal variation in the drivers of saltwater intrusion and wetland migration/habitat loss (White and Kaplan 2017). Some wetland types are much more vulnerable, freshwater forested wetlands are the most vulnerable when talking about wetland migration. The habitat of freshwater forested wetlands is decreasing with marsh migration and saltwater intrusion which is increasing the amount of ghost forests we see along the coast. This increase in ghost forests has been an interest for scientists for a while now but is growing in public attention due to the clear visual they provide of climate change. These changes are clearly seen through remote sensing practices, and Dr. Elliott White talks about his paper showing the net loss of 13,682 km2 of loss in coastal forested wetlands along the coastal plain (White et. al. 2021). He shares his experience in learning and engaging in remote sensing methods. Remote sensing can take less time, less money, less permitting, and less maintenance of field equipment than field science. Additionally, remote sensing provides us the ability to scale up and collect information at larger spatial scales. After Dr. Elliott White’s talk, the participants had a discussion on what information we would like to have to better understand vulnerabilities to SWISLR impacts along the NACP. Participants were invited to list their data wishes if no collection limitations were applied. About 27 unique ideas of data to include when accounting for NACP vulnerability were brought up. Participants were then asked to look at their data wishes and tell us of current data or useful indices that can be used to show the information participants want. About 16 of the 27 ideas currently had data sets, remote sensing abilities, or proxies available. The information collected is a growing database of data needs for the SWISLR RCN. You can see the board of ideas that were brough up here. We know that while many groups are having the conversation about how to carry out SWISLR mitigation efforts, not all groups have a seat at the table or are even consulted. This excludes valuable voices and perspectives while also creating the conditions for already vulnerable groups to shoulder the bulk of the consequences of SWISLR without being recognized. In addition to the regional differences of SWISLR, the climate impacts are not evenly distributed and often those who have the most to lose often have the least capacity to deal with the impacts of climate change. The goal of this webinar was to discuss this issue of exclusion.

Dr. Ryan Emanuel leads us through some though provoking questions and valuable resources surrounding this historical issue of exclusion. He began by asking “Who is at the preverbal table where decisions are being made about SWISLR?” He later questioned the need for this table at all, and if there are better ways to communicate SWISLR mitigation efforts. In an ideal world, decisions being made reflect consensus among people who participate in these decisions and those who contribute information. If the people who participate, or contributions being made, don’t capture the diversity or perspectives on the issue at hand, then decisions made might not meet the needs of communities that have much at stake. Additionally, many decisions do not end up reflecting the consensus. An example of vulnerable communities being left out of the management plans is the Jean Charles Choctaw Nation in Louisiana. The relocation strategy that the Jean Charles Choctaw Nation originally came up with has since been changed without their engagement by the state of Louisiana who secured the funds for the relocation plan. This lack of engagement resulted in plans that would have harmed the Choctaw Nation community and ultimately that relocation has not actually happened. Addressing issues in environmental planning in meaningful and culturally appropriate ways is more than just insuring raw participation. It is also about how we do the science that accompanies mitigation planning. The research we do is likely to become incorporated into the management and planning along the coast, therefore we need to do our due diligence to include the voices and methods of the vulnerable communities. A global review of how indigenous voices are included in our research found that the vast majority of climate studies practice an extractive model in which we use Indigenous knowledge systems with minimal participation. If we, as researchers, hope to make meaningful contributions to society than an effort needs to be made to include the communities of our study locations in deciding where to conduct the research, what questions to ask, and the methods we use. This idea of inclusion should also be extended to the institutions that serve marginalized individuals. A great resource to better our science is AGU’s Thriving Earth Exchange. The zoom room was primarily filled with individuals affiliated with universities, working with other universities or state agencies, and researching environmental science. Through our discussions we concluded that coastal residents do not want to know what is causing the flooding they are currently dealing with, instead they want to know how to fix it. However, our skill sets don’t mesh well because we don’t have the answers on how to fix it. Our roles in as scientists or researchers makes it difficult to provide solutions for people who just want to know what we can do to stop the SWI impacting my crop field. Instead, our information is becoming inconvenient and upsetting. Additionally, people on the ground are experiencing frustrations due to seeing some things work and some things not with seemingly no reason. A focus on community informed research is needed if we are to create inclusive solutions for climate change impacts. |

AuthorsKiera O'Donnell:[email protected] Archives

March 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed